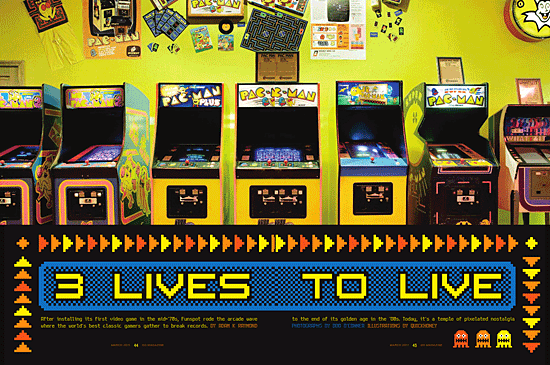

By Adam K. Raymond | Photos by Bob O'Conner | Illustrations by QuickHoney

On Nov. 18, 2010, on a typically frozen day in Weirs Beach, NH, Jason Cram did something that no person before him had ever done. He scored 38,248,380 points on the classic arcade game Zoo Keeper, setting a world record and accomplishing a goal he’d spent thousands of hours and hundreds of dollars to reach.

Today, there’s less pressure. Cram isn’t playing Zoo Keeper—he’s teaching it. And I’m his student. The premise of the game is simple, if a little unrealistic: The player controls a smiley little redhead named Zeke, whose girlfriend, Zelda, is being held hostage by a monkey. To make matters worse, this malicious monkey has unlocked all of the cages, releasing rhinos, snakes, elephants, camels and lions to hinder Zeke’s cause. The boy’s mission is to recapture the animals and rescue Zelda. My mission is to keep him alive. And also, on Cram’s advice, to not follow the game’s rules. “You’re supposed to trap all the animals in cages, but that’s not the way you score the most points,” he says. “You’ve got to let them out, then jump over them.”

|

This is my first time playing Zoo Keeper, and doing it in front of the world’s great- est player has got my left eyelid doing that twitchy thing it does when I get nervous. I grew up playing classic games like Tetris, Space Invaders and Centipede, but not the way they were meant to be played. I played on TVs, laptops and phones, controlling the game with a touchscreen or a crumb-filled keyboard. Since I was wearing diapers dur- ing the arcade boom of the ’80s, I wasn’t able to play games in arcades while listening to Culture Club—until I did what every classic game fan should do: I went to Funspot, the world’s largest arcade and home to the American Classic Arcade Museum. |

Funspot is a paradise of wholesome pleasures, with bowling, bingo and, coming this summer, a zipline park. It opened in Weirs Beach (part of the city of Laconia) in 1952, 20 years before Pong was released, with an indoor mini-golf course as its main attraction. In 1964, owner Bob Lawton bought 21 acres, adding a driving range and two theme parks (now closed)—but no addition was as important as its first arcade game: Atari’s Tank II. “It was mid ’75 or ’76,” Lawton says. “That game took in more than all of our other games combined.”

Tank II was like a Porsche among Pintos, hypnotizing teenagers while filling Lawton’s pockets. “The next summer we brought in Sea Wolf, which made $90 a day, and Indy 4, which brought in $140 a day. That’s when we knew the direction we needed to go,” he says.

According to the History of Computing Project, the years from 1971 to 1983 were “the golden age of video games.” During that time, there were 10,000 video game arcades in the US, says former American Amusement Machine Association president Michael Rudowicz. Funspot rode the wave of video arcade fever, opening outposts throughout the state and one in Florida (all have since closed). “You couldn’t keep people out in those years,” Lawton says.

And then Nintendo and Sega Mega Drive/Genesis arrived in the mid-to late-’80s, allowing kids to play games without being encumbered by, say, pants. As home console gaming grew, arcades began to die. By 2003, the number had dwindled to roughly 2,500.

In 1996, Gary Vincent, a Funspot employee since 1981, suggested gathering all of the dusty classic arcade games into one room and turning it into a museum. The American Classic Arcade Museum was born.

Fifteen years later, the museum is a cave of nostalgia and dull red lights that attracts gaming fans from around the world. Some 280 arcade games are crammed onto the third floor of Funspot (as well as 150 games in storage, awaiting donations to be restored), each one bleeping and blooping, screeching and howling, zoinking and bashing as if ALF was still on TV. |

|

Unlike most museums, this one can’t be fully appreciated without touching the exhibits, and there’s a lot to get your hands on. Among the army of games are 139 joysticks, 37 steering wheels, nine guns and four periscopes. There are also four types of Donkey Kong, six kinds of Pac-Man and 23 pinball machines. There are puzzle games, outer space games and even one game that challenges you to serve beer to thirsty patrons as fast as you can. The small portion of the museum not covered by games is plastered with classic posters and kitschy memorabilia, and the speakers cycle through a playlist of artists whose careers probably didn’t last as long as a can of Aqua Net. Walking around this altar to Atari with a pocket full of tokens makes me feel like I’ve just stepped out of a DeLorean in 1985.

“I pretty much spent my entire childhood at the arcade,” Cram tells me. After falling away from games as a teen, he and his wife, Anna, stopped by Funspot on a whim about a decade ago. “We haven’t left since,” he says. Today, the 32-year-old auto mechanic and his 33-year-old electronics technician wife are among the best classic gamers in the world. Jason holds eight world records on games like Congo Bongo, Kozmik Krooz’r, Lazarian and, of course, Zoo Keeper. Anna is second place in several games and holds two pinball records.

Both are part of a com- munity that treats Funspot like sacred ground. Every summer, hundreds of gamers in Konami T-shirts converge on Weirs Beach for the International Classic Video Game Tournament, which appeared in The King of Kong, the 2007 documentary about two guys attempting to win the Donkey Kong world record. (If you want to know the world records of pretty much any game, just ask Twin Galaxies, an organization that tracks them with an astonishing degree of detail. Curious what the high score for Zoo Keeper was before Cram broke it? The website will tell you it was 35,732,870, set by Cram’s brother

Shawn on Feb. 8, 2004.)

“We’re like a big family,” Anna says of the hardcore group of classic gamers. It’s a family that’s largely male and middle-aged. Most of the faces on Funspot’s Wall of Fame belong to guys who broader society might label as nerds. They’re computer programmers, bank comptrollers and physicians. And, to some degree, they’re all hungry for a taste of their childhood.

|

“If you walk into a room, turn on an arcade game and fire up some ’80s music, you can’t help but be transported back to being a kid. It’s like a time machine,” says Victor Laurel, a 39-year-old IT architect and classic game disciple on his first trip to the holy land. Laurel’s obsession has led him to purchase 28 arcade games (more than his house can hold). The appeal, he says, lies in their ability to transport him back to the days of stuffing his face with candy while burning through quarters at Shaky’s.

But nostalgia isn’t the only draw; it’s about the kind of gameplay, too. “I don’t want to say games were simpler back then because they can actually be much more complex than modern games,” Jason says. “But older games are definitely less intense.” (Anna, for example, likes memory games that challenge people to remember where things are.) |

Perhaps this is because of what hindsight reveals as bare-bones approaches. In Q*bert, you make an orange bug-eyed cartoon jump around blocks on a pyramid. In Food Fight, you control a boy named Charley Chuck who’s trying to eat an ice cream cone before it melts. Neither of those games contains anything close to the graphics or the immersive worlds of popular modern games like Call of Duty, but they can be just as captivating. Using only one button and one joystick to figure out strategy, learn patterns and master the speed of Tetris is a completely different experience from using the 14 buttons on an Xbox controller to go to war with an army of hungry zombies. Classic gamers don’t need or want life-like graphics, cinematic camera work and orchestral music. It’s a different kind of escape, similar to the simplicity people

look for in retro 8-bit music or cross-stitching.

They’re also after an experience that’s more personal than trading insults with an anonymous teenager on a headset. As my game of Zoo Keeper is quickly and embarrass- ingly coming to an end, a child, who’s probably tired of hearing his dad ramble about Pole Position, bumps into me. Friends egg each other on at a nearby Mario Bros. game. An employee nods hello to Cram and empties a token machine. That, combined with the catchy songs and blips and explosions com- ing from the stations around me, makes it sound like I’m in a casino.

“That’s why playing in an arcade is so much better,” Cram says, as Zeke narrowly avoids a marauding pack of camels. “At home you can get rid of the distractions, but arcade games were meant to be played in an arcade, with kids running around, people watching you play and all these distracting sounds.”

I wish I can blame it on the distractions, but truth be told, even if it was dead silent, my poor, pixelated friend Zeke never would have been able to dodge that fatal coconut. Game over.